I’ve been a fan of Mary Stewart’s romantic suspense novels for a long time. There’s just something about the plucky heroine with the complicated romantic past, thrown into Adventures that turn out to be connected with those same complications. Preferably in an interesting setting and with suitably scary stakes. And, of course, a murder or two.

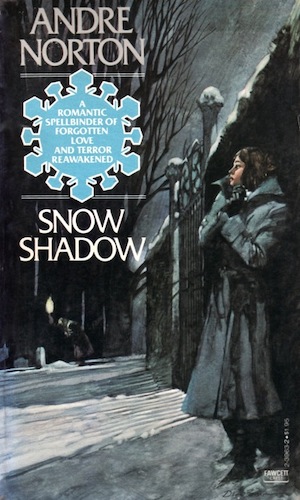

Snow Shadow is Andre Norton’s entry in the genre. It was first published in 1979, and it’s very late Sixties/early to mid Seventies. The attitudes, the eccentricities, the fashions—that awful plaid coat which plays such an important role in the plot. The elderly lady who affects the clothes and morals of the year she was born (with furious broadside against the horrors of Victorian decor—Norton did so, so hate it). The drug ring, the forgery ring, the spy, the stone-cold killer. It’s solidly grounded in the genre.

So is the protagonist. In this incarnation her name is Erica Jansen and she had the obligatory loveless upbringing by a stern aunt with a rigid sense of propriety and zero tolerance for children. Aunt Otilda is mercifully dead now and Erica is financially independent, with a decent career as a midlist writer—and a love affair, now five years past, with a handsome and charming man who turned out to be married.

Erica is a confirmed spinster, and she’s left her much-loved apartment in New Hampshire to spend a couple of months researching her next book in a small town in Maryland. The same town, as it happens, in which she loved and lost the darkly alluring Mark Rohmer. Whom she’s done her best to forget, but she’s never succeeded.

Soon after she arrives in Ladensville, her friend and colleague persuades her to move out of the bed and breakfast she’s been staying in and take a much nicer room in the mansion in whose carriage house the friend has been living with her husband. The mansion is called Northanger Abbey, and was owned by a passionate Jane Austen fan by the name of Austin (he kept trying to prove that, despite the slight variance in spelling, he was related to the great author). Dr. Austin died and left his estate in trust, with the stipulation that the money only be used to add to his collection of Austeniana. His daughters, now elderly, have either married their way out of poverty or, in the case of the daughter who inherited the house and the trust but not the means to support the house, done what they could to survive. Miss Elizabeth takes in boarders and subsists on the income.

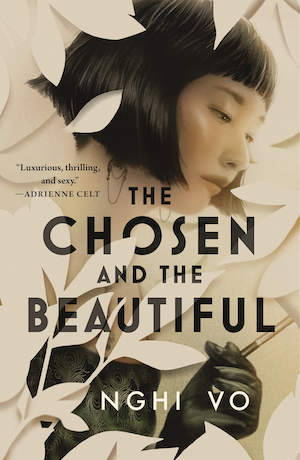

Buy the Book

The Chosen and the Beautiful

There’s plenty of mystery and dysfunction in the Austin family. The sister who married money goes away for a rest cure and abruptly dies. Her black-sheep son turns up dead. Her wounded Vietnam-veteran son remains offstage, but his drab wife and his sickly son are instrumental to the solving of the mystery of who killed the no-good son and his mother and tries to kill Miss Elizabeth. As to the why, there’s an Austen manuscript that is probably forged, but the late doctor’s collection just has to have it.

The supporting cast is reminiscent of an old-fashioned mystery house party. The femme fatale to whom Erica takes an instant and ultimately justified dislike. The writer friend’s sadly faded charmer of a husband. The pleasantly soothing family friend who turns out to be something else altogether. And, as the murders pile up, the hard-boiled police detective and, to Erica’s profound dismay, none other than Mark Rohmer, secret agent.

Mark, in the best tradition of the romantic-suspense hero, is not at all what Erica thought he was. She tries to avoid him, but he’s at the center of the investigation, and she keeps being pulled into it by a combination of her presence in the house and her insatiable curiosity. She spends a great deal of time tramping around the grounds in a series of snowstorms, being stalked, chased, and nearly killed, and Mark spends a fair amount of time either rescuing her or collaborating with her to find and capture the bad guys.

In the end of course she discovers that her assumptions about him were pretty much universally wrong. And of course that means she hasn’t gotten over him at all. Nor has he gotten over her. At all. Romantic suspense is often about a second chance at love, and it certainly is here.

Norton’s extreme discomfort with romance in general doesn’t mess things up too much. Romantic suspense a la Mary Stewart tends to be quite virginal and minimally sexy. Erica gets to obsess a little bit over Mark’s physical charms, but for the most part she frets about how he cheated on his wife, and how she can’t forgive him for that. His explanation for what she thought happened satisfies her, and he tops it off with a passionate declaration of soulmatehood accompanied by a very special ring which he has been carrying around for five years.

That’s an odd thing, and speaking of discomfort, I found it a little too much of its time as we say around here. Mark is Native American, and the ring and the vows that go with it are obviously lovingly researched. His side of the misunderstanding is that he thought Erica rejected him because her aunt taught her to be a racist, but that barely even pings her radar. She’s horrified because she thinks he was unfaithful to his wife.

What makes this painful for me to read in 2020 is the undertone of racism in the writing and in Norton’s own expressed attitude. She wants to be anti-racist and diverse and do justice to her Native character, but this passage bounced me off hard:

I felt the old pull and kept reminding myself that there were darker sides to his nature. He could be as cruel as his Blackfoot ancestors had once been said to be.

It had never bothered me that Mark was Indian. In fact, that had added to his attraction. Though education and wide travel had divorced him from what one might expect of his race, I was sure that under that outer shell he must be governed by the mores of another people.

That’s…um. Wow. Ouch.

Especially since one of the themes of the novel, which Erica spells out explicitly, is that nurture supersedes nature, and how a child is raised can overcome her heredity. Apparently that only applies to white people. Non-white people will inevitably throw back to their savage (a word she uses to apply to Mark) genetics.

This has to have been an ingrained belief, because it’s the actual plot of her time-travel novel, The Defiant Agents. From 1962 until 1979, her attitude seems not to have changed. She’s still nice white lady Doing Justice to the savage red man.

It doesn’t do anything for Snow Shadow to make Mark a Native American. It’s a gimmick. Let’s make the sexy guy a sexy savage Other, just for fun and to be all liberal and tolerant. It doesn’t have anything to do with the plot and it doesn’t make a serious dent on Erica except for the little frisson of the exotic. When he declares her his soulmate in actual transliterated, presumably Blackfoot language, it reads to my 2020 eyes as a straightforward case of Nice White Lady syndrome. She tried, but, no. Really. No.

By the way it is a complete coincidence that this article is posted a day later than usual as Tor.com observes Columbus Day, or as the governor of my state has decreed, Indigenous People’s Day.

That aside, this is a nice readable example of romantic suspense. It’s not brilliant; it doesn’t have anything like the wit or sparkle of Mary Stewart. It’s serviceable.

Next, for a bit of variety, I’ll go back to the mid-Fifties in Norton’s career and see what I think of one of her historicals, Yankee Privateer.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Since then she’s written novels and shorter works of historical fiction and historical fantasy and epic fantasy and space opera and contemporary fantasy, many of which have been reborn as ebooks. She has even written a primer for writers: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.